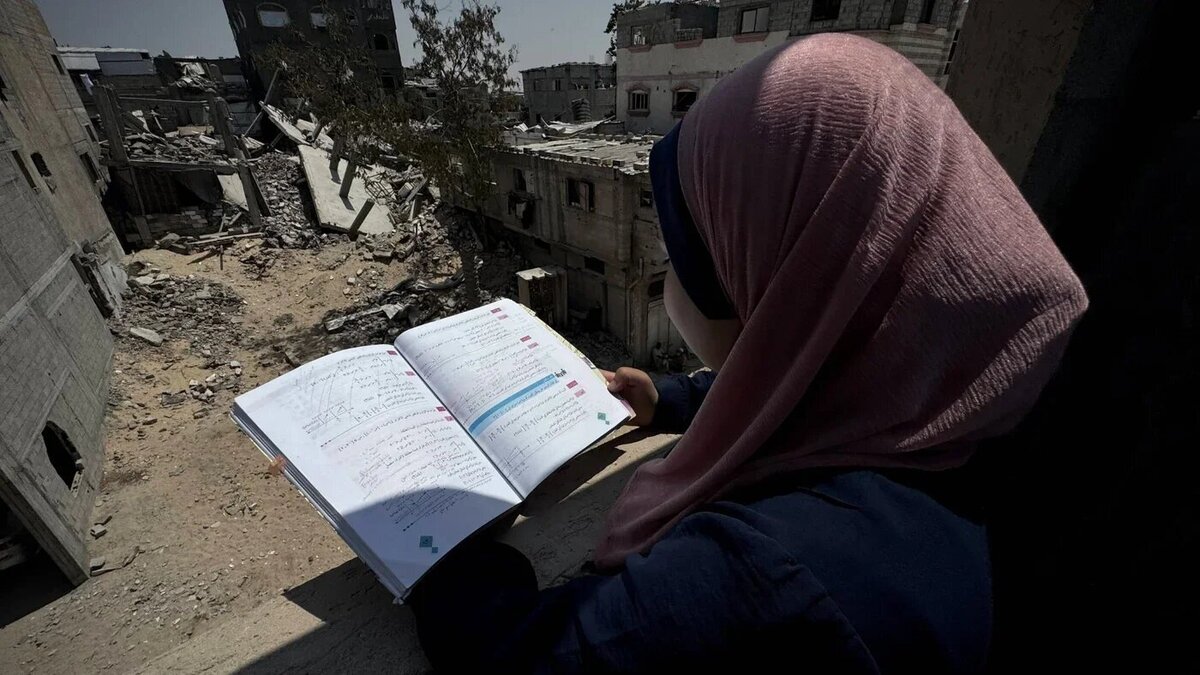

Dreams under the rubble: Gaza’s children still cling to hope of learning

Two years of Israeli warfare on Gaza have brought education in the besieged enclave to a standstill. With 97% of schools destroyed or damaged, nearly 600,000 children are now entering their third school year under the clouds of war and instability.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) announced yesterday that schooling for 300,000 Palestinian students in Gaza will resume after two years of devastating conflict.

According to UNRWA’s statement, the agency is implementing programs to restart education. Around 10,000 children will study in designated shelter centers, while the rest will learn remotely with the help of about 8,000 teachers.

The long suspension of education due to Israel’s two-year assault—compounded by the earlier COVID-19 disruptions—has left thousands of Gaza’s children unable to read or write, a crisis that human rights groups warn cannot continue.

Education in Gaza halted on October 8, 2023, following the outbreak of Israel’s destructive war. Many public and UNRWA schools were converted into shelters for displaced families, while others were completely or partially destroyed.

According to the Palestinian Ministry of Education, as of September 16, 2025, Israel had destroyed 172 public schools and bombed 118 more. Over 100 UNRWA schools were also destroyed or damaged.

The toll on Gaza’s education sector is staggering: 17,711 students killed, 25,897 injured, 763 school staff members killed, and 3,189 injured.

The Guardian recently reported that the denial of education has cast Gaza’s children’s futures into deep uncertainty.

A Gaza student living in a tent in what is called the “safe zone” of Al-Mawasi recalled her last day of school before the war:

“On October 7, I was in fifth grade—the last day I ever went to school. The air-raid sirens echoed in the hallways. Some kids cried; others held our hands tight. I remember wishing for a normal day—a class, a break, a poem. Instead, that day became the last page of my old life.”

She added: “I live in a crowded shelter with my parents, two brothers, and my sister. The tent walls flap in the wind; they protect us from neither heat nor cold. We queue for water and food. Some friends message me when they can—they say they’ve lost their schools but keep their old notebooks like treasures from a vanished world. I once dreamed of becoming a teacher, now I dream of becoming a journalist—to write, to speak, to show the world what it means to be a child in Gaza.”

When there’s internet, she studies online. Sometimes, volunteers teach small math and Arabic classes in makeshift tents.

“In those moments, I feel alive. The war took our homes, schools, families, and even my city Rafah—it’s all rubble now. But the greatest loss is education, because losing education means losing the future. I want the world to know: our dreams must not die. Gaza’s children deserve books, schools, and safety. Education is not a luxury; it is a basic right.”

A teacher from Al-Bureij refugee camp said: “I’ve been teaching in Gaza for over a decade—in Khan Younis, Deir al-Balah, and now in Al-Bureij. Before the war, I taught six classes of about 40 students each—240 young minds eager to learn. When the war began, my school became a shelter for families fleeing bombs. Soon after, it was completely destroyed. Now it’s hard to find a single intact school in Gaza.”

She continued: “Many of my students are gone—children who once dreamed of becoming doctors, artists, teachers. The surviving ones live with hunger and exhaustion, yet they still long to learn. When the internet allows, we share short messages, short lessons, small sparks of connection amid chaos.”

Across Gaza, teachers, volunteers, and NGOs are trying to teach wherever possible—in tents, damaged classrooms, or crowded shelters.

“Many of us are parents, too,” the teacher said. “I have three children whose education has been deeply disrupted. Their days are spent queuing for water or gathering firewood. Childhood has been replaced by survival. I remind them—as I remind my students—that knowledge is power.”

Nine-year-old Sara from Gaza City remembered the first day of the war:

“When the bombing started, my father came to take me from school. I never saw that classroom again. The army besieged the school, attacked those sheltering inside, and destroyed it completely. I lost my math teacher—she and her family were killed in their sleep. I’m scared to sleep now.”

She said: “I miss feeling normal. I miss being a student. I’m too young to be a genocide survivor. If I die, I don’t want to be remembered that way—I want to be remembered for my dreams. I wanted to be a doctor, to heal and give hope. But without school, that dream feels impossible.”

“Two months ago, I stopped studying entirely because of the heavy bombardment. It feels like what’s left of my childhood is being stolen. I wish the world could see us—not as numbers in the news, but as children who just want to learn, play, and live. We deserve to dream.”

Seven-year-old Ismail, now in Cairo, recalled his kindergarten in Al-Maghazi: “I loved learning and knew all my letters by heart. I couldn’t wait to write my own stories. Then the war began—school ended. Our home was bombed, and we fled. We left everything behind—our toys, clothes, even my favorite crayons. As we ran, I saw my friend’s body in the street.”

“Every morning, I watch Egyptian children walk to school in their uniforms. I wish I could be one of them. My mother found an informal school for refugees. It’s not recognized, and we won’t get certificates, but even a few hours of learning is better than nothing.”